submitted by Eman M. Vovsi

submitted by Eman M. Vovsi

(the author is thankful to all Napoleon-Series contributors who mentioned in their posts, in different time, various paper soldiers’ collection discussed below)

Once upon a time, in a little town of Strasbourg, there was a baker/flour merchant named Christian Boersch (around 1780-1824) who painted charming little soldiers…

The story, which begins as a fairy tale, is not only true but enables us today to know the uniform worn by the thousands of men who passed through Strasbourg – France’s principal fortress facing Prussia – on their way to the battlefields of Europe. It was time when the streets of Strasbourg almost continuously resounded to the tramps of infantry shoes, the jingling of infantry harness, and the rumbling of iron-bound wheels of artillery batteries and supplies wagons. With the town population around 30,000 inhabitants, the permanent garrison ranged between 6,000 to10,000 men, above and beyond units constantly passing through the city. Not surprisingly, therefore, that some local armature artists, editors and book dealers, were inspired to try to capture this military pageantry and military drama in graphic form. When they were successful in so doing, their product found a ready market.

Boersch made and painted his paper miniatures with such care and detail that each figure seems to have actually lived the fantastic epic it represents. Little is known of this obscure Alsatian baker except that he was born at the outset of the French Revolution and died in 1861. His artistic development is attributed to the artistic development to the celebrated draftsman Benjamin Zix (1772-1811), whose niece Boersch married. Born in Strasbourg, Zix became known for his excellent painting of Swiss landscapes. In 1806 he was assigned, as a draftsman, to the Grande Armée HQ; at some point he also assisted famous Gros in his painting of the Battle of Eylau. Zix left us numerous sketches reflecting the every-day life of soldiers in their quarters in bivouac in Prussia, Poland and Spain, far different from the official salon painters.

B. Zis. French soldiers crossing the Danube, 1809

It was around 1810 that Boersch began painting his paper miniatures with the help of his uncle’s sketches and notes. Further, he was the first who invented the principle of mounting completed figures on wooden blocks. With the end of the Empire, Boersch interviewed retired soldiers living in and around the city, forming, little by little and with his son’s help, a fabulous miniature army lovingly conserved until 1971 in a local museum, when 4360 of his paper soldiers were sold at the auction in Angeres.

Boersch. Train d’artillerie de la Garde Impériale

Boersch. 9e régiment de Ligne

According to one opinion, the only figures which may properly be termed Petits Soldats de Strasbourg are those that were made by collectors who either:

– painted printed black-and-white sheets, or

– designed their own figures, had them printed and then painted them, or

– made each figure entirely by hand

In the case of printed sheets – whether engravings, woodcuts or lithographs – paper soldiers could be divided into three categories by the method of reproduction:

– First, editors who commissioned the artist and a printer to create sheets at the editor’s direction

Example: during the period of the First Empire one of them was certain Barthel of Strasburg, but majority of his works falls around 1820s. He was one of the first editors to complement his sheets of row-upon-row of soldiers with sheets portraying troops in a variety of occupation – in bivouac, fencing, or street life.

– Second, by painters acting as their own editors

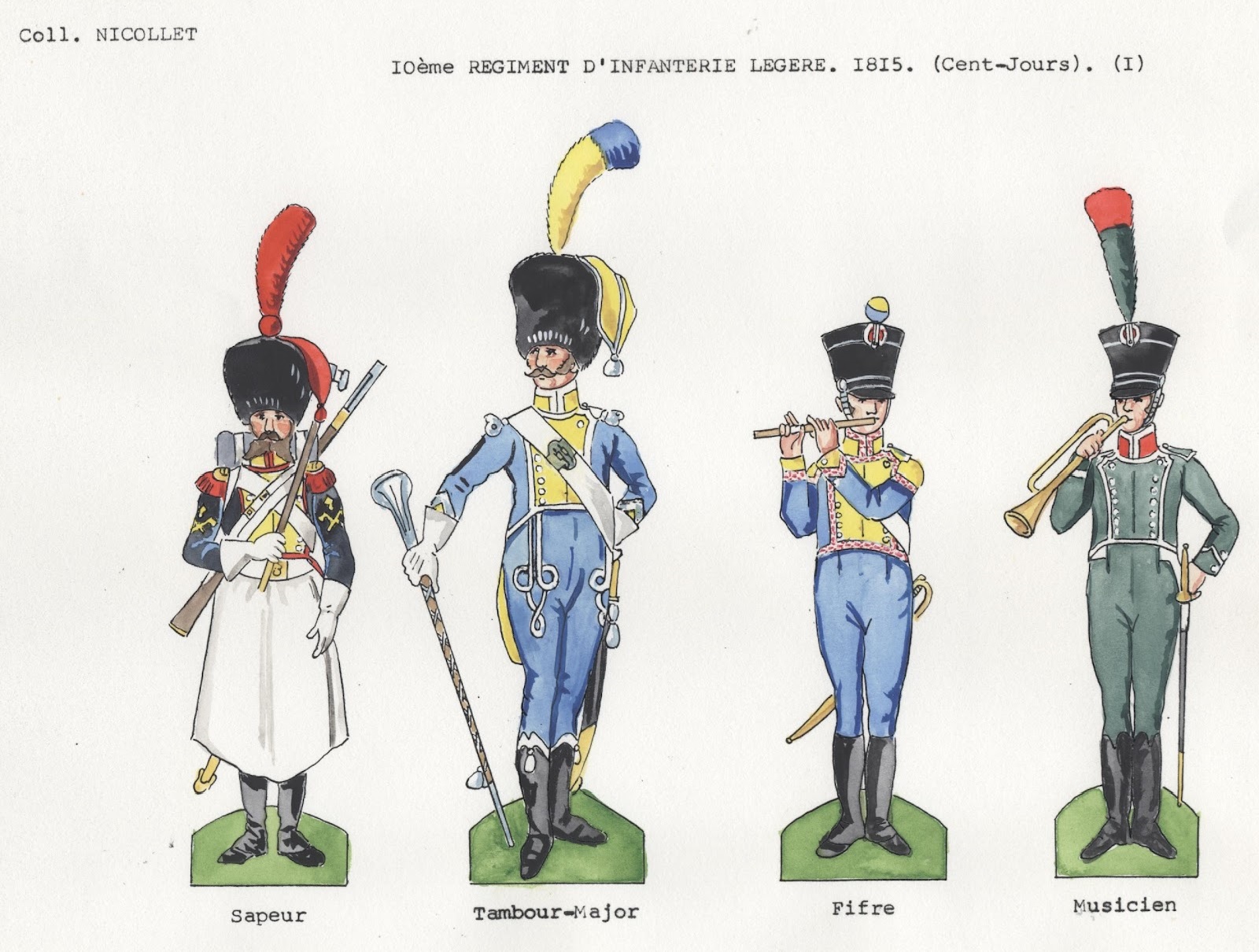

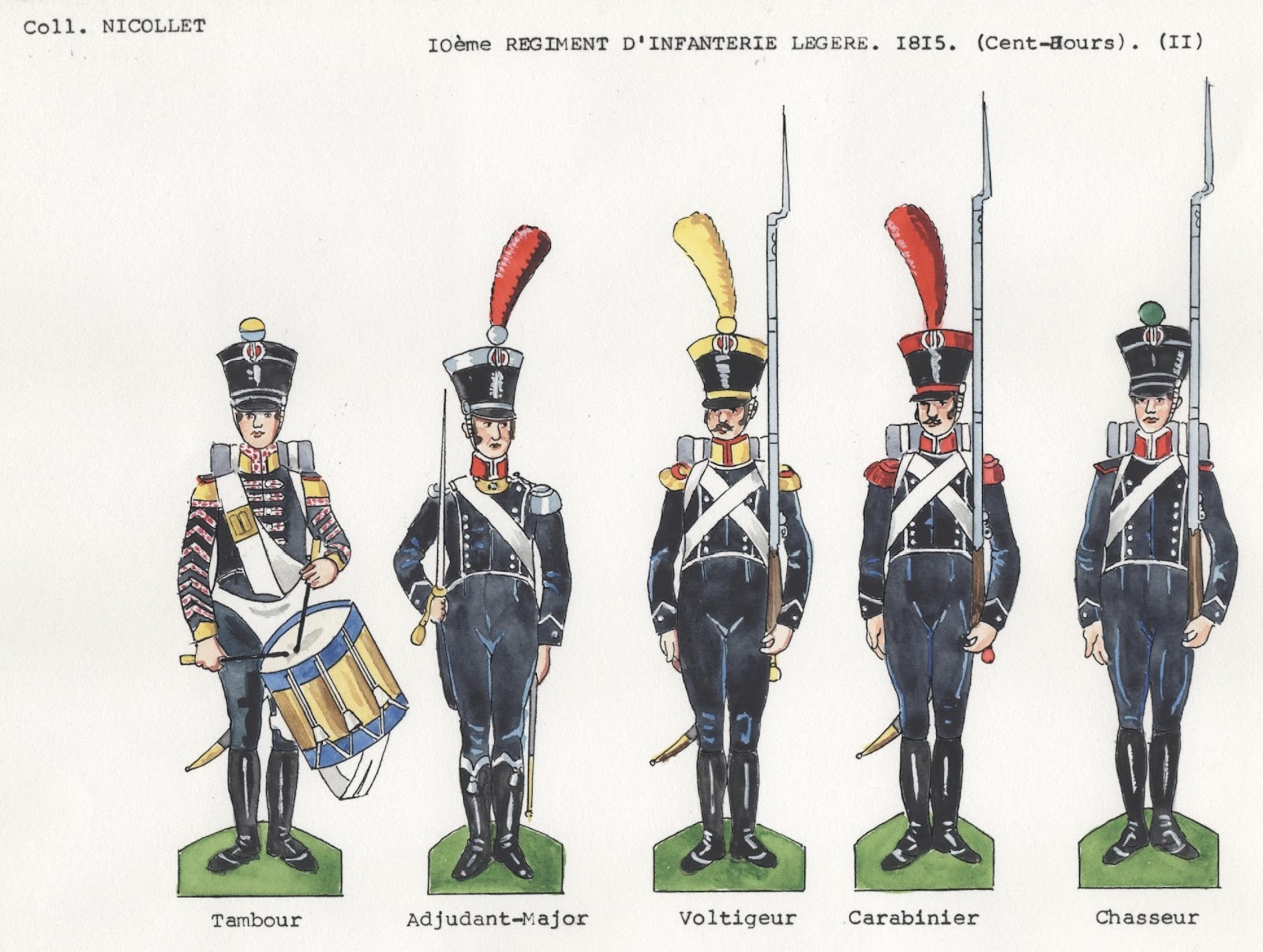

Example: Eugène Nicollet (1801-1865), an officer of the National Guard who, in 1817 has commenced his collection with his friend, Achille Roederer by painting his first soldiers and was continuing to do so for over 50 years. In common with a number of printers, he had a way of getting double use out of some of his designs of soldiers, by simply adding dotted outlines showing what, for example, a tricorn hat would look like instead of the bearskin cap that was the soldier’s “primary” headgear. In addition to designing his own figures, Nicollet also painted the printed sheets of Barthel (originally, published uncolored). Since Nicollet was at his late teens when he began his collection, his earlier works might contain certain mistakes or anachronisms.

Nicollet. 10e régiment Légers, is primarily showing soldiers wearing 1812 uniform Regulation as was reproduced by the French artist, Henri Boisselier (1881-1959) after the WWII.

– Third, by artists who commissioned printers to run off their drawings

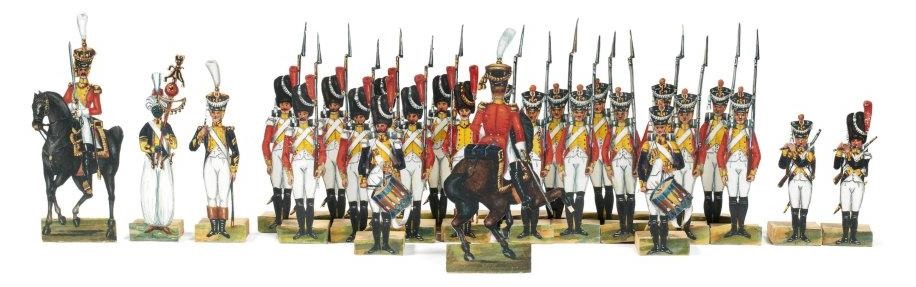

Example: this is the most definitely the Würtz family, who completed his “Napoleonic” collection somewhere between 1825 and 1840 (or by 1855, according to other sources). They are very pretty, but despite E. Ryan claim that they are “the most accurate and complete depiction of the troops of the First Empire, Guy Dempsey asserts that they still should be regarded as secondary source for they were completed decades after actual events. Next, it is also problematic that each unit of soldiers with all possible ranks and types of soldiers (drummers, officers, voltigeurs, etc). Since it is extremely rare to find such completeness in primary source depictions of Napoleonic soldiers, it is possible that Wurtz was tempted to fill in gaps in his arrays based on theory and inference rather than on concrete information about uniforms actually worn. Finally, since the soldiers not accompanied by any notes of the artist, it is impossible to say for sure which sources were consulted.

On 1 October 1899, the major of medicine, Würtz, presented this collection (19 000) of his forefather as a gift to the newly organized Musée de l’Armée; they were placed on display in 1938 and are there ever since. Each foot soldier is approx. 10 cm high.

Würtz. 1er régiment d’éclaireurs (1813-1814): escadron de la Vieille Garde et escadron de la Jeune Garde, 2e régiment d’éclaireurs (1813-1814) et 3e régiment d’éclaireurs (1813-1814)

Wurtz. 3e régiment étrangers, vers 1811 (ex régiment Irlandais)

Fourrier compagnie de carabiniers, porte-drapeau, fourrier compagnie de voltigeurs et fourrier compagnie de chasseurs

Wurtz. 9e régiment d’infanterie de Ligne, 1809-1810.

Other producers:

Gustave Adolphe Henri Silbermann (? – 1870), was the first printer/editor to popularize paper soldiers on a major scale. His greatest contribution to the art of the paper soldiers was his development of a process for printing with oil colors. He began printing sheets of soldiers by 1845 starting with two sheets of First Empire line infantry (other 28 were dedicated to the Second Republic and Second Empire). Practically all his sheets were published in both colored and black-and-white versions.

Theodoré Carl (1837-1904) who specialized in the First Empire, designed his own figures which were then printed various publishing houses. He produced nearly 10 000 figures, which are now on display at the Strasburg Museum of History.

Drawings after Carl’s original paper soldiers: Grenadiers et Chasseurs à pied dela GardeImpériale(1804-1814). Catalogue of theStrasbourgMuseumof history by Darbou (around late 1960s)

Modern drawings of Theodor Carl’s soldiers based on the catalogue composed by Darbou

Plate 1. Grenadiers et Chasseurs à pied dela GardeImpériale(1804-1814)

Fritz Boeswilwald, a draper merchant of Strasbourg, who primarily copied soldiers produced by Boersch, Nicollet and Würtz. He started his collection around 1845 (See French magazine Uniformes 61 for more details)

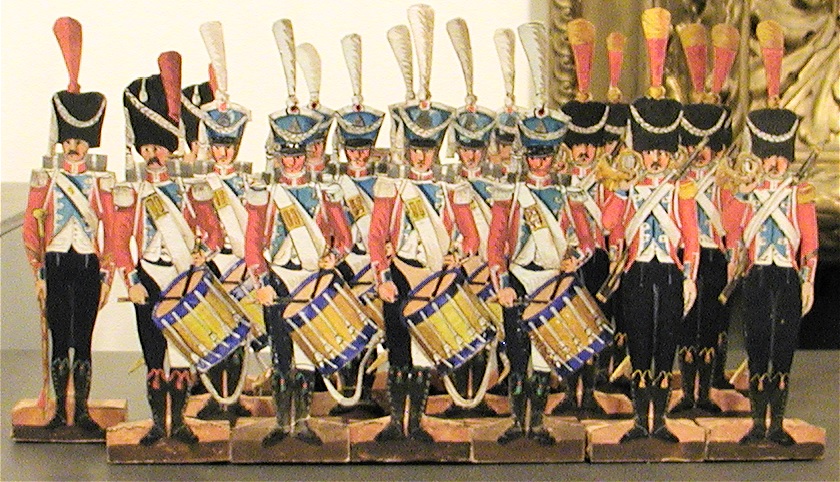

4e régiment de Ligne, 1810; paintings by Henry Boisselier (1881-1959) after Boeswilwald for Paul Schmidt’s album

Henri Gainier-Tanconville (1845-1936), had a reach family history of his forefathers serving in Napoléon’s armies who worked along the Strasbourg historian Frédéric Piton.

Jules Antoine Maillot (?-1893), captain of the National Guard in 1837, he was inspired by the style of Boersch and Wurtz

1st Swiss regiment (Maillot Collection)

In his famous book on paper soldiers, Edward Ryan examines the Commandant E.-L. Bucquoy’s research and concurs that “the great error of the Strasbourg painter/collectors… was to extrapolate their excellent documentation into representation of complete regiments, so that sound information became intermingled with incorrect assumptions. For example, taking as a point of departure his drawings of a drummer of fusiliers, a sergeant of grenadiers or an officer, such a painter would design the entire regiment, making errors as he went… Note [however] that during the period of the First Empire, some regiments had as many as seven battalions scattered to the four corners of Europe, each drawing on local sources of supply and tailors to replenish or renew their worn uniform.” As a result, these collections “pitilessly furnish all ranks for all regiments. One sees drum major and standard-bearer for regiments which had none, and complete mounted band for regiments created at the end of the Empire, which in all probability did not have one.”

Summing up note that these wonderful collections was created primarily by the armature authors living, by their own accord, the “Napoleonic legend” they were too young to witness or take part in… But, nonetheless, they wanted to depict this one of history’s most colorful period for posterity and we thank them for their efforts.

Sources consulted:

Rigo, “Paper Veterans,” transl. Robbie Trombetta, Campaigns No. 9.

Edward Ryan, Paper Soldiers. London: Golden Age Editions, 1995.

Jean-Marie Haussadis, “La collection Würtz du Musée de l’Armée,” Uniformes No. 106-107 (1987), pp. 49; 50-51